How to build a best-in-class job architecture for your organisation

Job architecture brings structure and logic to the way roles are defined, levelled, and compensated within an organisation.

By introducing consistency to job titles and how roles are defined, job architecture ensures that compensation decisions are consistent and that employees are clear on their responsibilities and progression opportunities.

Plus, with a job architecture in place, organisations can better support internal pay equity – vital with incoming legislation like the EU Pay Transparency Directive.

To help you get it right, we spoke to two leading experts in the field: Figen Zaim, Founder of Olivier Reward Consulting, and Rob Green, Founder of Darwin Total Rewards and an Associate with MCR Consulting.

Drawing on their insights, this step-by-step guide walks through how to structure a job architecture that’s not only effective, but also practical, scalable, and built to last.

💡Table of contents

- What is job architecture?

- Job architecture vs job evaluation vs job levelling – what’s the difference?

- Why is job architecture important?

- The role of job architecture in skills gap analysis

- How to structure a robust job architecture: a step-by-step guide

Subscribe to our newsletter for monthly insights from Ravio's compensation dataset and network of Rewards experts 📩

What is job architecture?

Job architecture is a structured framework used to bring consistency in how an organisation defines and groups job roles, levels, and career pathways for employees.

Once built, a job architecture can then act as a visual ladder for your organisation – mapping the pathways from entry level roles all the way to the most senior positions.

According to Figen Zaim, Founder of Olivier Reward Consulting, many organisations and leaders think of job architecture in the wrong way – particularly mistaking job architecture for organisational design.

“We’ve had many job architecture projects where company leaders think we’re coming in to re-organise their functions or move roles around – because they aren’t aware of the difference between job families (groupings of similar jobs with common skillsets and career paths) and organisational functions (the operational layout of the company which also governs reporting lines),” she says. “They don’t understand job architecture should be generic and should never take into consideration who reports into who.”

Instead, a job architecture acts as a vertical hierarchy: a scalable structure of job roles, levels, and functions, not reporting lines.

“You can use that vertical hierarchy to ensure consistency and fairness in almost every single process in the People Team,” Figen explains, “including the way you hire people, how you promote them, what the pay band is for each level, and even who gets a Macbook versus a Windows laptop.”

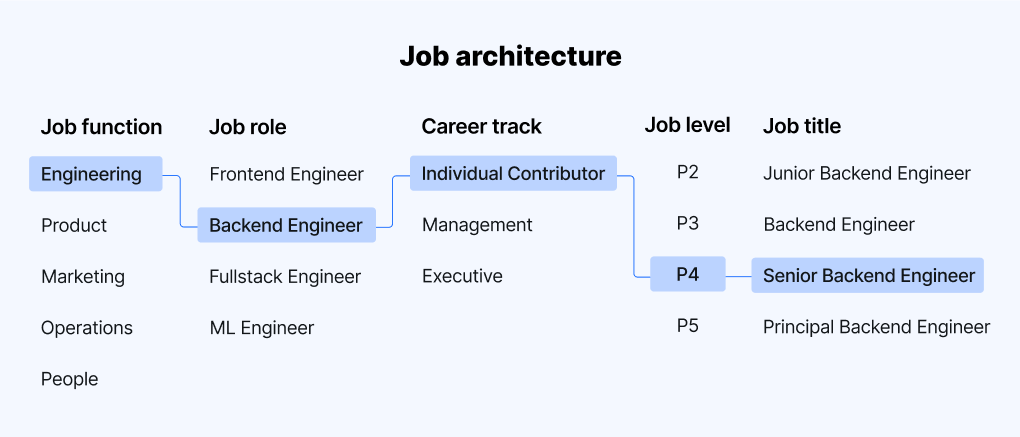

Because job architecture can vary in complexity depending on the size of the business and industry, there’s no one template to follow. However, there are core components that every job architecture should have:

- Job functions or families. Families of related positions that share similar skill sets, responsibilities, and career paths within the company (e.g. Engineering, Marketing, or Sales).

- Job titles. Individual job roles that sit within each job function (e.g. Engineering Manager, Head of Product Marketing, or Account Executive) – including consistent job title conventions.

- Job levels. The hierarchy of seniority within each job role, that reflects differences in skills, experience, and scope of responsibility – typically split up into professional / IC, management, and executives. Well-defined levels also allow each employee to see their potential career pathways.

- Job descriptions. Clearly defined responsibilities, skills, and competencies for each role. In recent years, skills-based hiring has become a more popular approach, leading companies to focus more heavily on skills as a core element of job architecture.

“A job architecture creates a vertical hierarchy of job roles, levels, and functions – but not reporting lines. In this way it can be used to ensure consistency and fairness in almost every single Rewards process.”

Founder of Olivier Reward Consulting

Job architecture vs job evaluation vs job levelling: What’s the difference?

Job architecture, job levelling, and job evaluation are often used interchangeably, but they’re not the same thing. Each plays a distinct role in how you structure jobs, define seniority, and make fair compensation decisions.

As Rob Green, Founder of Darwin Total Rewards and Associate at MCR Consulting, put it: “It’s all interconnected, but if you’re looking at it simply, there’s a clear cascade: job architecture sits at the top, then comes your job roles, then levelling, then evaluation,”

Let’s break it down.

Job architecture: The overarching framework

Job architecture is the broad framework that acts as an internal map for how roles are defined, grouped, structured, and compensated.

Key elements include:

- Job families and functions

- Job titles

- Career pathways

- Compensation elements such as salary bands and bonus eligibility

Once that framework is in place, job levelling and job evaluation come into play.

Job levelling: Defining seniority

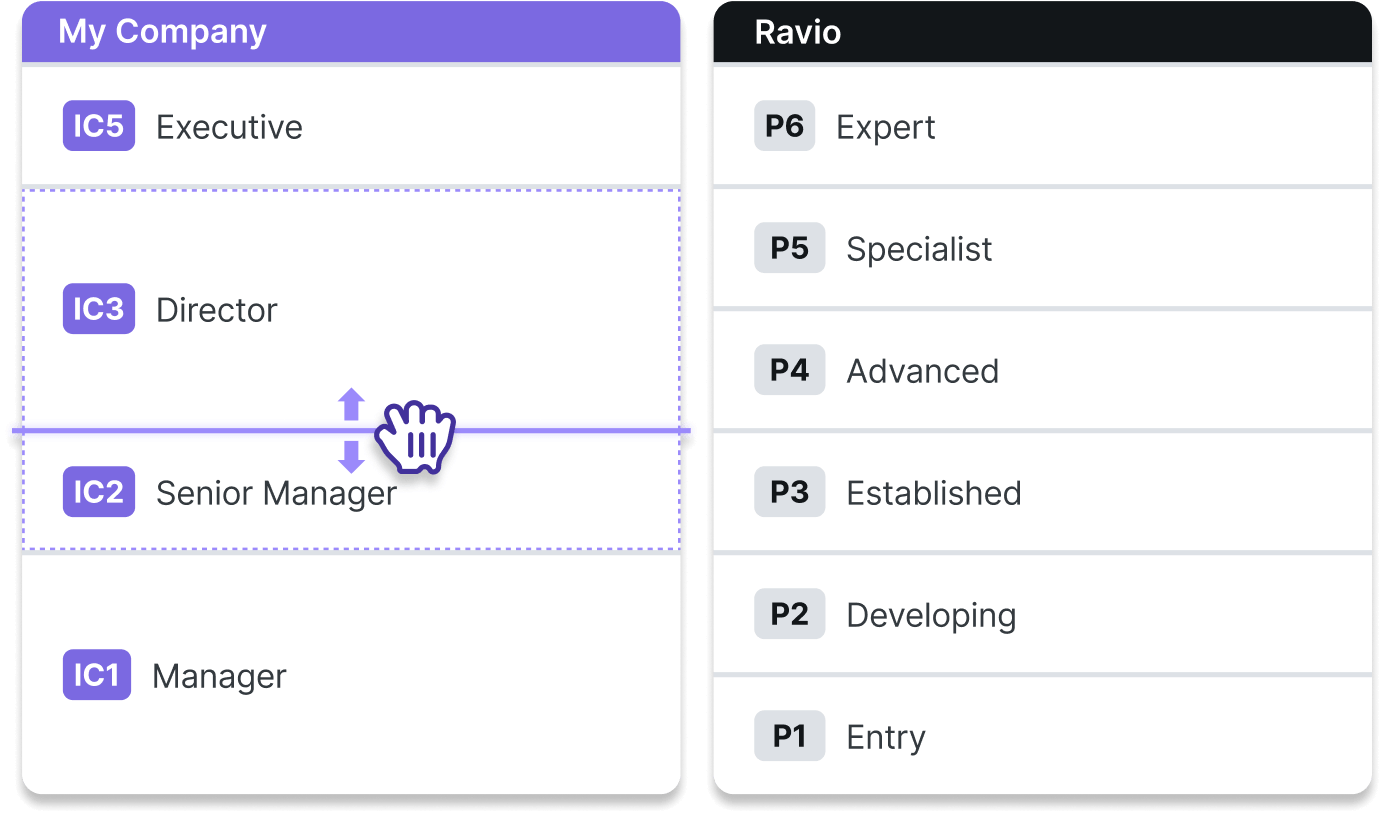

Job levelling defines the hierarchy of seniority. It clarifies what each level means across different career tracks such as IC (individual contributor), a manager, or an executive. Level descriptions then also set clear expectations for progression at each level.

A well-structured job levelling framework typically includes multiple levels within different career tracks, such as:

- Professionals or Individual Contributors (P-level), where employees are measured by their expertise and impact rather than managerial responsibilities.

- Management (M-level), who oversee teams and are evaluated based on leadership and team performance.

- Executives (E-level), who shape strategic direction and drive business impact.

“Job levelling is the backbone (within job architecture): knowing what levels you have, what they mean, and what the key differences are between levels supports Talent and Rewards management within an organisation.

Founder of Darwin Total Rewards and an Associate at MCR Consulting

Job evaluation: Clarifying the value of each role

Job evaluation is the process of determining the value of a role based on its responsibilities and impact – which then guides how each role is compensated relative to one another.

There are different methods for job evaluation, including:

- Job ranking. Every job within a company’s organisation structure is ranked (e.g. from 1-100) based on the relative business impact of each role.

- Point-factor. Jobs are scored using a pre-defined points system, with points assigned to compensable factors such as skill level, autonomy, and decision-making responsibilities

- Factor comparison. First, a set of compensable factors is agreed (like skills level, autonomy, and decision-making responsibilities). Then a few example job roles are evaluated to determine the level of each factor involved in that role. Then the salary for these roles is divided into each factor to define the relative rate of pay per factor – which can then be used to determine the monetary value of other roles.

- Market pricing. Jobs are evaluated based on external salary benchmarking data, to determine the fair market rate (and therefore relative monetary value) of each role.

“Job evaluation is the high value piece of the jigsaw. It gives an organisation clarity on what differentiates job levels based on key criteria and factors, to reflect the internal reality within an organisation”.

Founder of Darwin Total Rewards and an Associate at MCR Consulting

Why is job architecture important?

Through a standardised approach to job titles, job role descriptions, and job levels throughout an organisation, job architecture enables consistent decision-making on compensation and career progression, which brings much-needed clarity for employees.

Here are the five key reasons that job architecture is so important:

- Job architecture provides role title clarity

- Job architecture enables reliable salary benchmarking comparisons

- Job architecture supports pay equity and compliance

- Job architecture enhances employee understanding on career progression and engagement

- Job architecture supports skills-based workforce planning

Let's take a closer look at each.

1. Job architecture provides role title clarity

As companies grow, job titles often become a mess – created ad hoc, negotiated individually and often inflated, or used externally for status. Job architecture helps untangle this mess by applying clear naming conventions and ensuring titles are used consistently across the business.

For example, one “Head of Product” might be managing a team of 15 and driving strategic decisions, while another with the same title is an individual contributor with no direct reports.

Equally, someone might hold a “VP” title simply because they joined early or negotiated well, despite having the same scope as a Senior Manager elsewhere in the business.

This causes a cascade of problems: colleagues with similar roles but different titles and pay, employees confused with different reporting lines, and promotion pathways that become political rather than performance-based.

Figen Zaim has seen this happen time and time again, where emotional attachment to titles can lead to real, long-term problems for businesses.

“Job titles are so emotive. No one wants to be told they’re no longer Head of Reward but now a Senior Manager,” she says. “But if you make an exception for one person, then a manager does the same for their team, suddenly two exceptions become twelve. Where do you stop?”

2. Job architecture enables reliable salary benchmarking comparisons

Salary benchmarking only works if the internal structure behind your data is sound. One of the most common (and costly) mistakes companies make is rushing to benchmark roles without first organising their job architecture.

Rob Green sees this regularly, as his client companies want to know whether they are competitive or not against the market they are attracting and retaining talent from.

"Companies often jump straight to market data – but without a job architecture in place, the numbers won’t match your internal reality,” he says, “you’re benchmarking blindly."

To benchmark salaries accurately, you need job titles that reflect actual responsibilities, levels that describe scope and experience, and a clean mapping of roles across the business.

Companies with five variations of “Software Engineer”, each with different scopes and pay will never be able to reliably benchmark against the market.

It’s important to get the underlying structure right, because accurate comparisons with market data are a must for competitive compensation.

"Job architecture doesn’t just ensure employees are paid fairly compared to peers – it also keeps you competitive in the market. When internal structures can be accurately aligned with benchmarks, businesses are better able to attract top talent and reduce the risk of losing out to competitors."

Chief People Officer at Ravio

3. Job architecture supports pay equity and compliance

In Europe, the upcoming EU Pay Transparency Directive will soon require companies to publish gender pay gap reports, conduct joint pay assessments when pay gaps exceed 5%, and disclose salary ranges to both employees and candidates. Employers will also be expected to prove that pay differences are not discriminatory, ensuring employees are being paid fairly for work of equal value.

That’s where job architecture is critical.

For Figen, a job architecture is the gateway for having objective and transparent conversations with employees.

“It allows you to actually talk and say: this is how we levelled your role, this is where you are, this is what your band is,” she says. “You can make that story make sense – from a structural point of view.”

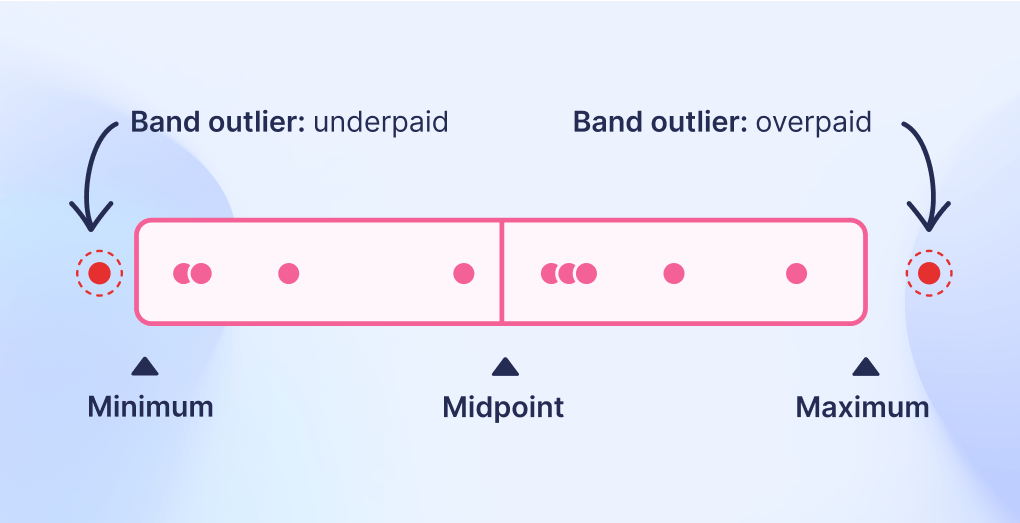

And with salary bands layered on top of that structure, organisations can identify meaningful trends or salary band outliers.

For example, you may not spot that your highest-paid people in a level are all men, or that women are clustered disproportionately in lower bands.

This structural clarity is what enables consistency across all decisions, not just pay.

“The benefit of building a generic job architecture is that it brings longevity and fairness. You’re not redoing it every time your structure changes. It’s robust enough to support analysis around pay equity or performance-based pay.”

Founder of Olivier Reward Consulting

4. Job architecture enhances employee understanding on career progression and engagement

If People and Reward leaders can’t clearly define and communicate the structure of roles and levels within the organisation, employees are left in the dark about what their role entails, how they compare to peers, and what career progression looks like.

This lack of clarity makes it difficult for employees to see their potential growth within the company, leading to frustration and disengagement over time.

In fact, a 2022 Lattice survey found that 67% of US employees want more transparency from their organisation about pay practices.

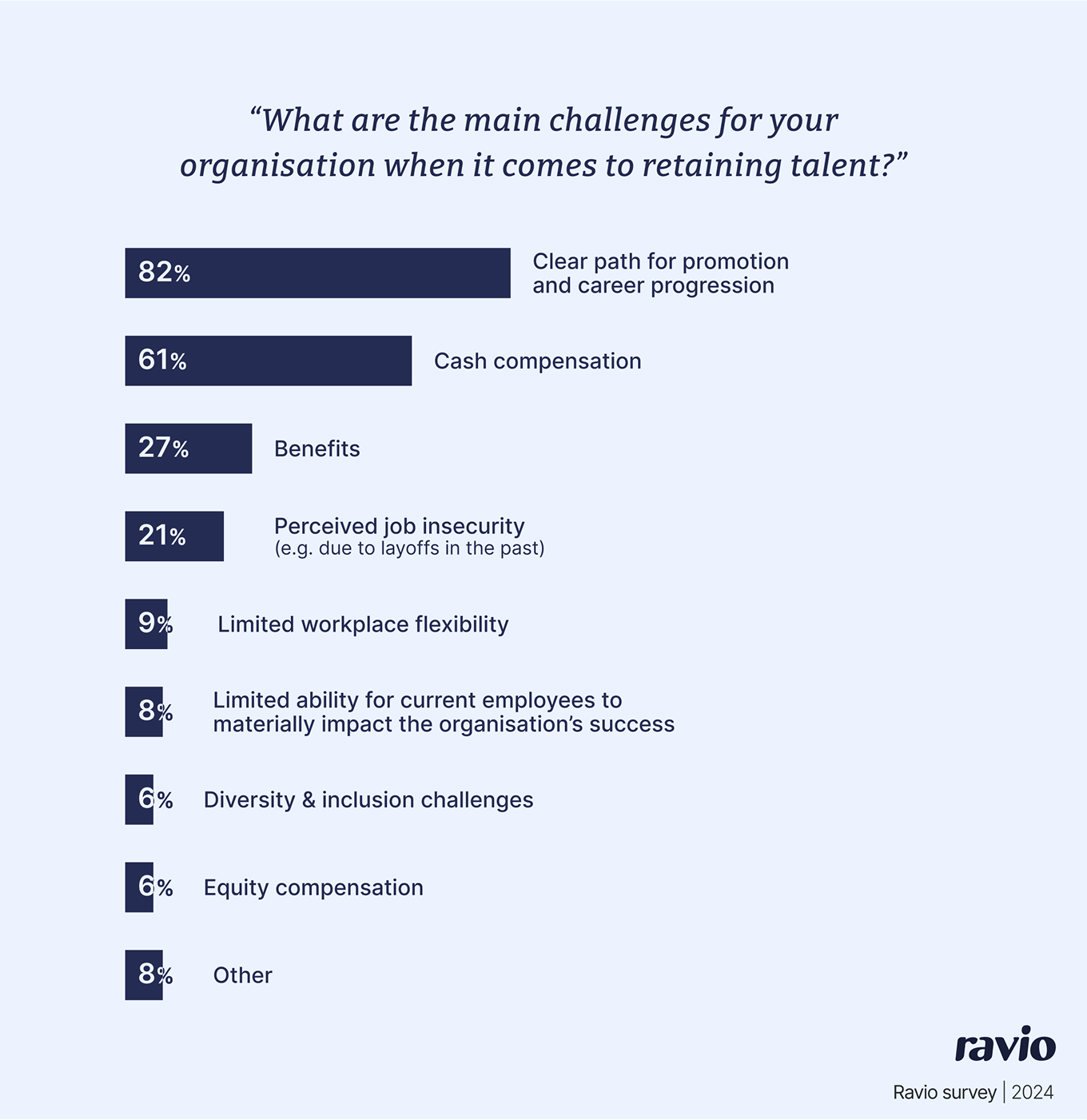

And in our latest Ravio Compensation Trends report, a lack of clarity around promotion and career progression topped the leaderboard for why organisations are struggling to retain talent – so it’s clear that employees want that clarity over pay and progression.

Figen explains that in her experience, questions from employees can become difficult (if not impossible) to answer when that structured foundation isn’t there – and this is a clear sign that it’s time to work on a job architecture to bring clarity.

“If your employees are asking ‘How can I move to the next level?’ or ‘How can I explore sideways moves in different functions?’ and you don’t have an answer, that’s your sign you need job architecture.”

Founder of Olivier Reward Consulting

Many organisations are responding by adopting more open and structured career frameworks to build trust and fairness into their progression practices.

For some, like Typeform, this means introducing open salary bands within job functions, allowing employees to see the ranges and levels associated with their roles.

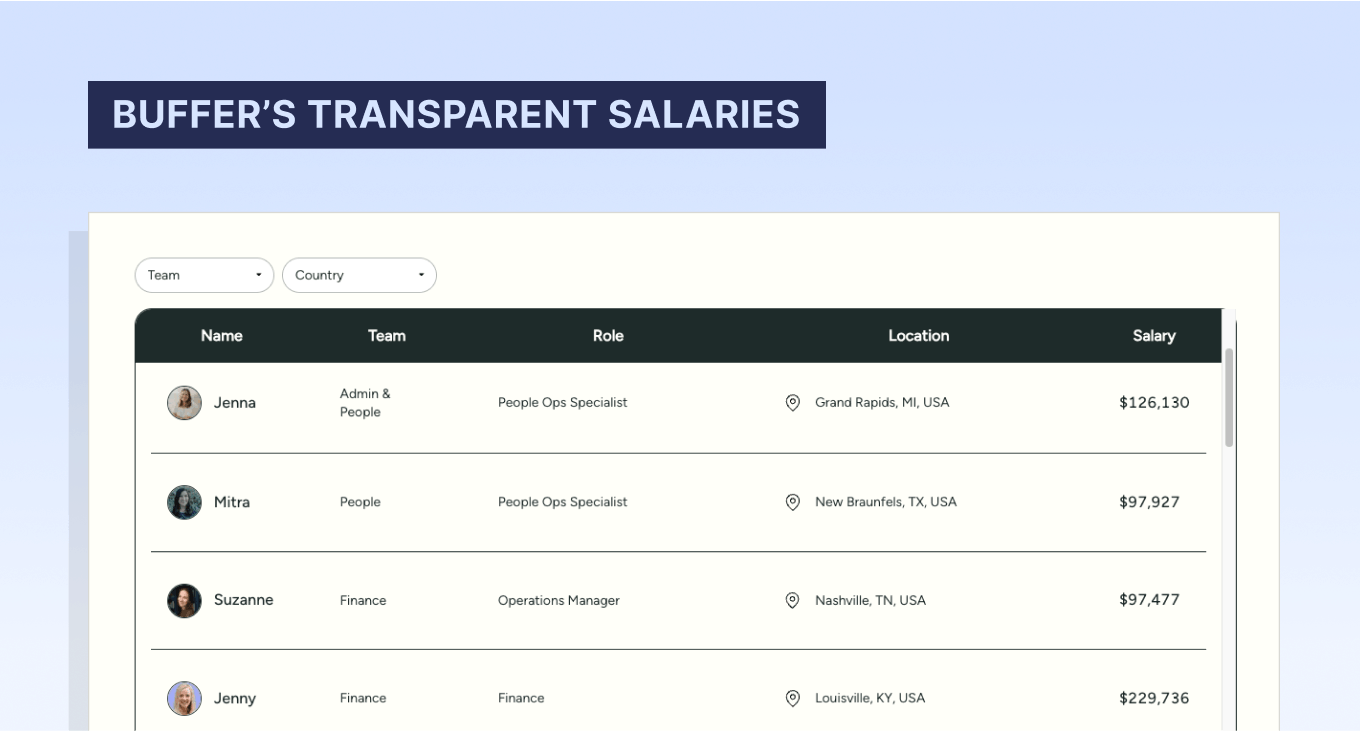

Other companies like Buffer prefer a more radical approach by publicly sharing all employees salaries. This literal level of transparency isn’t for every company – and many experts don’t recommend this – but the underlying purpose of giving employees clarity around roles, expectations, and progression is the same.

5. Job architecture supports skills-based workforce planning

Traditionally, a lot of emphasis has been placed on factors like years of experience or a relevant degree when hiring for new job roles.

However, there’s been a recent shift towards skills-based hiring and skills-based pay – where there is much more focus on the skillset of applicants and how this aligns with business needs.

It enables companies to be much more flexible in terms of hiring profiles, whilst also helping to fill skills gaps within the organisation.

This skills-based approach is becoming more and more popular, so it’s an important consideration.

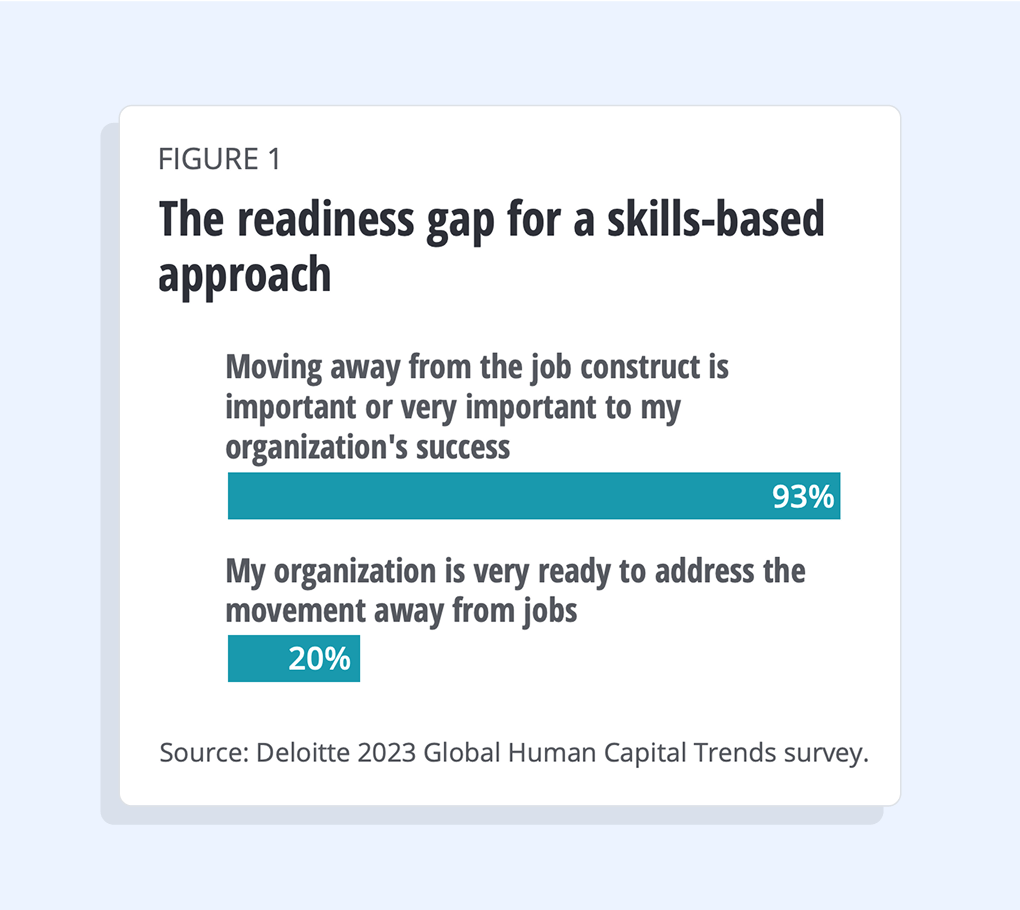

In fact, according to Deloitte, 93% of organisations believe moving to a skills-based job architecture is crucial for success today – citing performance pressure, the need for agility, talent shortages and diversity and equity as key drivers.

For companies that want to adopt a more skills-based approach, a robust job architecture ensures clarity around which skills are important for the roles and levels of seniority within the company’s structure – as well skills gaps analysis to identify skills that are currently missing within the company.

For example, instead of assuming that all software engineers need the same capabilities, a job architecture could break them down into key technical proficiencies (e.g. cloud computing, AI/ML, cybersecurity) and business skills (e.g. project management, stakeholder communication).

With this in place, HR leaders can then perform a skills gap analysis, taking inventory of existing skills and comparing them against business needs both now and in the future.

This level of granularity helps organisations identify gaps in specific areas rather than making broad assumptions about talent shortages.

Plus, it also helps to identify existing employees who might have clear opportunities to develop the right capabilities to fill those gaps, in support of their progression goals.

For instance, rather than hiring externally to fill a data science role, a company might identify employees in adjacent fields – such as business intelligence or software engineering – who could be upskilled through targeted training programmes. This can also be a huge bonus for employees who are keen to explore sideways moves or try out different departments, supporting more flexible career pathways.

It can also support a skills-based compensation approach, wherein employees are hired and compensated based on the skills and capabilities they provide rather than more subjective factors like their job title, previous experience, or degree qualifications.

"Job architecture doesn’t just ensure employees are paid fairly compared to peers – it also keeps you competitive in the market. When internal structures can be accurately aligned with benchmarks, businesses are better able to attract top talent and reduce the risk of losing out to competitors."

Chief People Officer at Ravio

How to structure an effective job architecture: A step-by-step guide

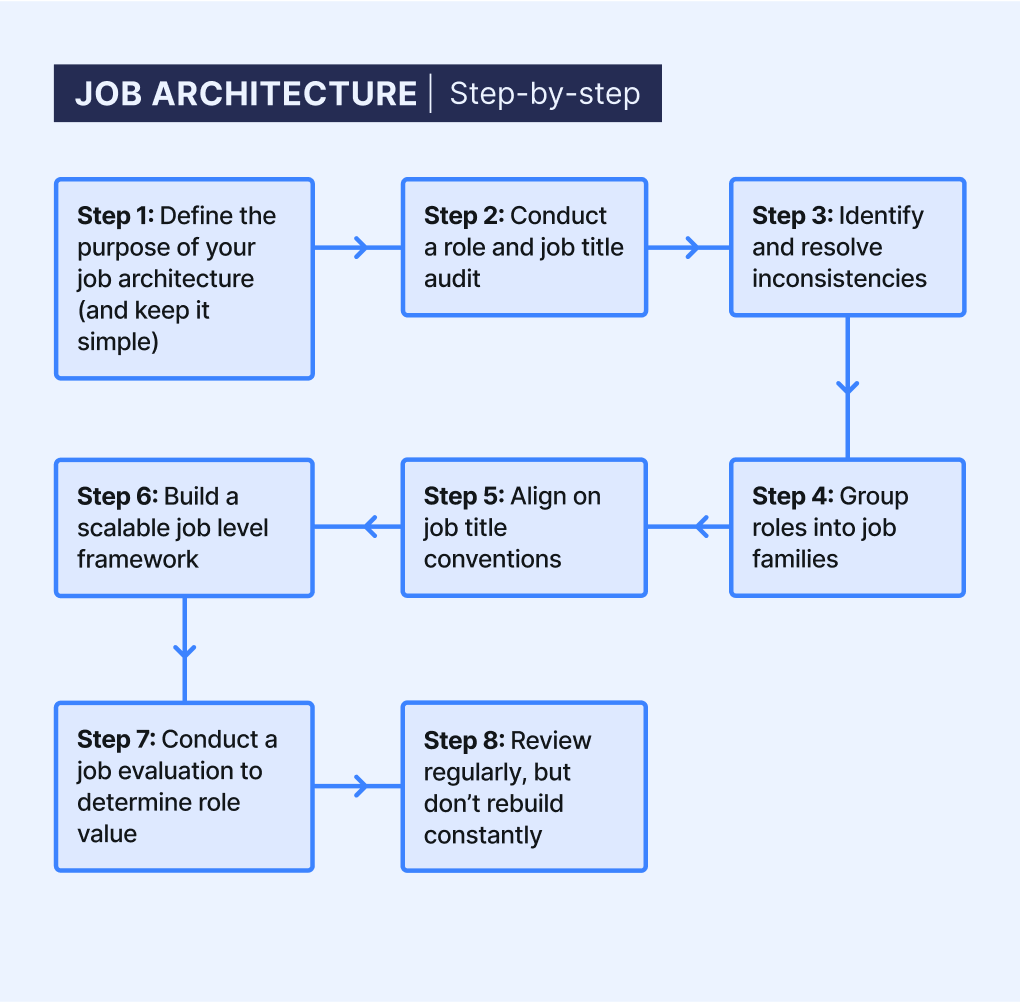

Step 1: Define the purpose of your job architecture (and keep it simple)

Companies introduce job architecture for different reasons – whether to improve pay equity, bring consistency to job titles, support growth, or give employees clearer career progression.

Whatever the driver, defining the “why” upfront helps align stakeholders and shape the right level of complexity from the outset.

When you’re deciding if it’s the right time to implement a formalised job architecture, Figen Zaim recommends considering your company size.

“You can apply a form of job architecture at any size, but the elements you choose to include depend on your needs and complexity,” she says. “If you’re small, keep it simple. Don’t build full-blown pay bands for 100 people – you’ll end up overengineering it.”

Step 2: Conduct a role and title audit

Start by auditing your current roles. This means cataloguing job titles, understanding core responsibilities, and grouping similar jobs – even if they have different names or sit in different teams. Focus on simplifying and removing duplicates.

For many companies, particularly those that have scaled quickly, title inconsistency is the single biggest barrier to clarity and accurate salary benchmarking, so this step is very important.

In one case, Rob Green had to audit over 1,000 job titles because the company had grown without a structured job architecture in place.

“I undertook a project to build a Rewards strategy with one company that had 1,000 job titles for 15,000 employees,” he explains. “We brought that down to around 120 roles. Without simplification, you’re just benchmarking blindly and will not fully understand the competitive market you are attracting and retaining from.”

Step 3: Identify and resolve inconsistencies

Once all existing roles have been documented, the next step is to identify inconsistencies in how similar roles are named, scoped, or compensated.

This is especially important for companies that have experienced rapid growth or never had a formal structure in place – where it’s common to find people doing similar work under wildly different titles or pay grades.

“I’ve seen companies where everyone calls themselves a ‘Head of’ at various levels of the organisation, including within the same function and sub functions” says Rob Green. “That kind of inconsistency makes it impossible to differentiate, benchmark, or plan for growth.”

Compare your mapped roles and titles against your intended job families (see Step 4). Highlight overlaps or redundancies so you can consolidate roles and clean up titles that no longer reflect the real work being done.

Step 4: Group roles into job families

After identifying role inconsistencies, the next step is to group jobs into clear, scalable job families – collections of roles that share similar skills, responsibilities, and career paths. These might include functions like Engineering, Marketing, Sales, Customer Support, or Product.

This step is where keeping it simple really matters.

Avoid the temptation to create overly specific job families for niche or individual roles. Instead, start broad and standardised, especially if you’re in tech, where job title sprawl is common. That means grouping roles into clearly defined families that reflect how talent is structured in the wider market.

For Rob, this is a mistake he often sees.

“So many companies have multiple titles within software engineering or data science,” he explains. “That just makes it super messy. I would always recommend starting with three core families in tech: Product, Software Engineering, and Data Science. I’m simplifying, but those three titles are a great starting point and allow Rewards to match the language to market benchmarks and apply best practice, for instance Data Science, BI, and Data Quality Engineers, within Data Science.”

Figen agrees, recommending that companies add core job families first (like Marketing, for instance) and then introduce more granular families later (like Brand Marketing or Content Marketing).

“I’ve had companies ask me to create a brand marketing job family for one person,” Figen says. “It’s just not worth it. Build what you need now, but with enough flexibility to expand later.”

By reducing complexity at this stage, you make it easier to benchmark roles externally, align compensation internally, and scale your structure as the organisation grows. It also helps you avoid bloated, unusable architectures that collapse under their own weight when your team evolves.

Think of your job families as the core building blocks of your architecture. Once these are in place, you can add specificity later.

Step 5: Align on job title conventions

A best practice is to establish a consistent and standardised naming convention. For example, decide whether titles should indicate seniority (e.g. Junior Developer, Senior Developer) or job function (e.g. Marketing Specialist, Marketing Manager).

Avoid overly specific or niche titles that might become redundant or confusing as the company grows. Once conventions are set, stick to them to maintain consistency across all functions.

Step 6: Build a scalable job level framework

With job families and titles in place, a job levelling framework then applies it consistently across all departments. Avoid creating bespoke level structures for each function, instead, use a single framework that reflects increasing levels of complexity, responsibility, and impact.

“Keep your levels generic,’ suggests Figen. “Create a structure that can flex across functions, and then add a marketing lens, or a tech lens, as needed. You don’t need to rewrite the framework for every job family.”

As we saw earlier, a typical structure includes:

- Individual Contributor (IC) or Professional (P): Measured on personal output and expertise.

- Manager (M): Measured on team delivery and leadership impact.

- Executive (E): Measured on business outcomes and strategic direction.

- Support (optional): Roles that provide operational or administrative support.

Each track then includes multiple levels (e.g. P1-P6) with clear descriptors for scope and expectations.

Those descriptors are important to ensure clarity and consistency in how the levels are applied across the organisation – as Rob Green put it: “the levels have to mean something”. “Line Managers and business leaders tend to know how many levels are in an organisation”, he continues, “but they can’t describe how many are IC, how many are managers, or what the progression looks like without insights and education from Rewards and HR .

Step 7: Conduct a job evaluation to determine role value

Once roles and levels are in place, job evaluation helps assess the relative value of roles so you can match them to salary benchmarks and allocate compensation fairly.

This can be done using formal methodologies like point factor, factor comparison, or market pricing – depending on the approach that makes sense for your company.

“Evaluation is where levelling really comes alive for the business” explains Rob Green. “It’s about understanding what actually differentiates job levels – such as Software Engineer Level 1 versus Level 2. This then provides key context for consistent Talent and Rewards management within an organisation, including hiring and promotions.”

As with everything else, the recommendation is to keep it simple to begin with. You don’t need to over-engineer evaluation, especially early on. Keep it focused and pragmatic, especially if you’re not a 10,000-person org.

Step 8: Review regularly, but don’t rebuild constantly

A well-structured job architecture should last years, not months – a structure that is robust enough to scale with your team.

But, your organisation will inevitably change, and your job architecture needs to flex with it.

So, conduct annual reviews to assess whether new roles or functions need to be added, and whether your structure still reflects how work is done.

Importantly, Figen highlights the importance of avoiding building something so bespoke that it becomes a burden to maintain.

“If you make your job architecture too detailed and too aligned to how your company works right now then you’ll have to change it every time you grow, restructure, or pivot,’ Figen says, “ And that’s just not sustainable.”

Instead, aim for a flexible foundation that supports your company’s evolution – whether you’re doubling in size, introducing a new product line, or entering a new market.